By Martin Walker

Your PC may well be the nerve-centre of your studio, so keeping it in top condition is worth a bit of effort. Read on for the SOS guide to inner and outer PC cleanliness.

There's no need to periodically reformat your PC and reinstall

everything from scratch to regain peak audio performance. Giving it a

good spring-clean will keep your hard drive error-free and your personal

data secure, relieve your drive of unwanted junk data and eradicate

hundreds and sometimes thousands of redundant entries in your Windows

Registry, which can slow Windows performance and sometimes cause

crashes.

Even physical cleanliness can make more of a difference to

performance than many musicians realise. Keeping your PC clean on the

inside will help it run cooler and reduce acoustic noise, by giving the

cooling fans less work to do, and may even prevent long-term crashes.

Just follow these tips to optimise your computer so that it never grinds

to a halt and runs cooler and more reliably than ever before.

Some musicians seem to take a perverse delight in never cleaning

their computers, but keeping your PC physically clean can have more

significant health benefits than many people realise. Studies have found

that a PC keyboard can end up contaminated with 400 times more germs

than the average toilet seat. A primary cause of this shocking health

risk is that so many of us eat near our computers, with the result that

germs and bacteria grow between and underneath the keys, as they do on

any other surface that's regularly handled, including your mouse,

telephone, and so on. This can result in ear, nose and eye infections,

and I've seen it estimated that up to 60 percent of time off work may be

caused by contracting germs from dirty office equipment. The most

germ-ridden item in many offices is the printer button, so it's fair to

assume that studio germs will also gather on the various sliders and

rotary knobs of our mixers and synths. If you run a commercial studio

the health issues resulting from lots of clients handling your computer

and audio gear may be even worse (especially since some people don't

seem to wash their hands after visiting the bathroom!).

For general cleaning of PC casework, a simple rub-down with a cloth

dampened with washing-up liquid and water, followed by a quick polish

with a dry cloth, is often sufficient and won't leave smears like some

general-purpose cleaning products. For more details, have a look at our

feature on 'Refurbishing Your Old Equipment' in

SOS December 2006 (

www.soundonsound.com/sos/dec06/articles/cosmeticsurgery.htm).

Other PC-related items that will probably benefit from a routine

clean include floppy drives (with a dedicated cleaner disk) and CD/DVD

optical drives, especially if you're experiencing unreadable disks or

audio stutter. In the case of the latter, cleaning the laser lens

assembly may help. You can do this using a dedicated lens-cleaner CD,

but sometimes a better long-term solution is to open up the drive and

clean the lens manually, using a cotton bud and isopropyl alcohol (

SOS reader and studio owner Tim Rainey has a helpful guide to the latter on his web site at

www.kymatasound.com/Optical_drive_fix.htm).

Your computer and other often-handled items in your studio will

generally benefit from dedicated cleaning products that not only avoid

smearing but also have anti-static and anti-bacterial properties. Most

PC component retailers stock some, but one range that particularly

caught my eye is from Durable (

www.durable-cleaning.co.uk),

especially as they promote awareness of health issues with their

'Computer Cleaning Week' (17th to 22nd September), which also has its

own dedicated web site (

www.computercleaningweek.com).

The Durable product range includes Superclean sachets and

anti-bacterial wipes that are suitable for PC and music keyboards, mice,

telephones, faders and knobs, plus Screenclean, for streak-free

cleaning of all types of monitor screen and other glass surfaces on

scanners and photocopiers. Meanwhile, to eject crumbs and other detritus

from inside your PC keyboard, try a Powerclean Airduster canister. The

dedicated Durable PC Clean Kit 5718 contains both Superclean and

Screenclean fluid, cleaning cloths, and keyboard swabs and cleaners that

reach between the keys to remove grime.

I was impressed when I tried out samples from the range. When I

up-ended my PC keyboard and tapped it, all manner of food crumbs and

dead skin particles dropped out, but the Powerclean Airduster dislodged

plenty more (it may help to use the soft brush of a vacuum cleaner

attachment to help remove any further debris). To clean the keys

themselves, I used neat Superclean with both swabs and the supplied

lint-free cloths, and it was surprising just how much grime ended up on

them, even though the keys looked superficially clean.

I found Superclean moist wipes perfect for cleaning and sanitising

mice (don't forget to wipe off the ingrained dirt found on the 'skids'

underneath), while anyone still using a ball mouse should open it up and

clean the ball itself, along with the rollers, which will keep your

mouse action smooth and sure. The moist wipes also worked very well on

telephones, rotary knobs, fader caps and music keyboards. I was

particularly shocked at how much dirt came off the last!

Desktop and laptop monitor screens may already have anti-reflective

or anti-static coatings, so don't be tempted to use domestic

glass-cleaning products that may strip these away. You can try a damp

clean cloth, but I found Durable's Screenclean not only easily removed

stubborn marks and left my screens clean and shiny with no smear marks,

but its anti-static properties really did seem to prevent further muck

accumulating. Overall I can highly recommend the range, which is widely

available at reasonable prices.

You

may have noticed web sites offering free automated Internet PC

checkups, which, once they have potentially discovered hundreds of

problems on your machine, then offer to sell you software to resolve

them. Unfortunately, the only ways to thoroughly scan your PC for

problems are to download and run a free utility or run Active X controls

and Javascript tests, both of which have the potential to do serious

damage to your computer. My advice is, therefore, to be extremely

careful and not to be tempted to run any such tests unless you're

absolutely sure the web site belongs to a

bona fide developer that's been in business for some time. One I've had recommended to me by an

SOS Forum user is PC Pitstop (

http://pcpitstop.com), but in general I find it hard to recommend such regimes.

Once the outside of your PC and peripherals are clean, the next stage

for the desktop PC user is to remove one of the case side panels, to

inspect the inside for any build-up of dust and dirt. You'd be amazed at

how much muck can build up on heatsinks and cooling fans, and the

problem may be particularly bad if you smoke or burn joss sticks in the

studio (so don't do it!).

Unfortunately the build-up of dirt generally occurs so gradually that

you may be surprised when you eventually suffer a major calamity. Even a

thin layer of dust on heatsinks and cooling fans reduces their

effectiveness, so the operating temperatures of your CPU and other

components in your PC will gradually creep up, which in turn may

increase acoustic noise as fan speeds increase to counteract the higher

temperature.

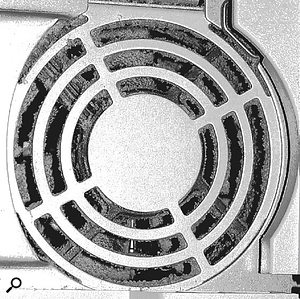

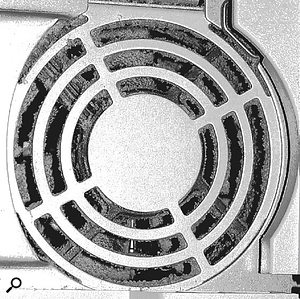

If

you can see this much caked-on dust inside your power supply, your PC

is probably running hotter than it should, and you should immediately

remove its side panel to give it a good vacuum.

If

you can see this much caked-on dust inside your power supply, your PC

is probably running hotter than it should, and you should immediately

remove its side panel to give it a good vacuum.

Without a

good clean, more severe symptoms are eventually likely to appear,

including songs suddenly glitching due to high processor overheads

(because the CPU has automatically throttled its clock speed down in an

attempt to cool it), or unexpected shutdowns. In the worst case a PC

will boot up fine, run for just a few minutes, and then shut down and

refuse to boot up again until it has cooled down. The latter is often

what happens when the gaps between the heatsink 'fins' become completely

solid with dirt, or when the cooling fan is so clogged up that it can

no longer rotate.

The diligent can monitor their CPU, motherboard and hard-drive

temperatures, along with fan speeds, using suitable software utilities

(for more details, read 'The

SOS Guide To Keeping Your PC Cool,

Quiet, and Stable'; see the 'Further Reading' box). However, a routine

internal inspection a couple of times a year makes more sense.

Unplug the PC from the mains and use a soft brush and a

vacuum-cleaner brush attachment to remove as much muck as you can find

from all the obvious places. These include the CPU fan and heatsink, any

case fans and any air filters (often placed before the intake fans at

the front of a PC). Don't forget to clean any other heatsinks you find

on the motherboard, or on expansion cards (modern graphics cards require

large heatsinks, as do some soundcards). For inaccessible fans, such as

those inside PC power supplies, moisten a cotton bud and use it to wipe

the fan blades, or blow an Airduster (described in the previous

section) into the PSU from the back of the PC to loosen the internal

dust, which should then get blown out by the fan.

Finally, for DIY desktop PCs, while you're inside the case, see if

it's possible to use cable wraps and ties to neaten up the wiring loom

connecting the PSU, motherboard, floppy, hard and optical drives. If you

can streamline the airflow by carefully forming the cables into neat

bundles, you may shave several degrees Centigrade off your CPU

temperature, and therefore be able to tun your cooling fans at slightly

lower speeds, for less noise in the studio. I heard of one PC user who,

after cleaning his machine and tidying up the wiring, measured

reductions of five degrees Centigrade for his CPU temperature, eight

degrees for his motherboard and a couple of degrees for his hard drives!

Laptops are often more difficult to open up for access to the air

vents and internal cooling fans. The procedure also varies considerably

from model to model, and may involve the removal of dozens of tiny

screws or struggling with lots of confusing clips. If you suspect

overheating due to an internal build-up of dust and dirt clogging your

laptop fans, and can safely get inside, clean the fans as above, then

use a blast of Airduster through the intake vents to dislodge any other

dust. It's best to do this outdoors, since you may get a sizeable cloud

of dust flying out.

If it's not obvious how to open up your laptop, one useful web site

linking to DIY instructions for many different models can be found at

http://repair4laptop.org/notebook_fan.html.

Failing that, it may be safer to return the laptop to the manufacturer

or a local repair company for cleaning. If you're considering an

upgrade, such as having more RAM installed, asking the company to give

your laptop a good clean while it's already opened up may be

significantly cheaper.

For

quite some years now, the vast majority of hard drives have featured

SMART (Self-Monitoring, Analysis and Reporting Technology), which

provides feedback about performance parameters including error rates,

spin-up time and temperature. Although in older computers the extra

overhead slowed performance slightly and resulted in many people

disabling SMART monitoring in the BIOS, with modern PCs this overhead is

almost undetectable.

When any of the parameters mentioned above

changes significantly, it may indicate impending failure, so you might

as well take advantage of the information to find out how your drives

are performing and whether or not they are likely to fail in the near

future. I've previously mentioned

HDD Health (

www.panterasoft.com)

in PC Notes as a useful utility that sits in your system tray and

predicts impending failure of your drives, but another I've recently

discovered is

HD Tune (

www.hdtune.com).

This utility not only provides SMART health status on demand, but also

offers drive benchmark tests and a useful error-scan function that will

find defects (bad blocks) on your drives.

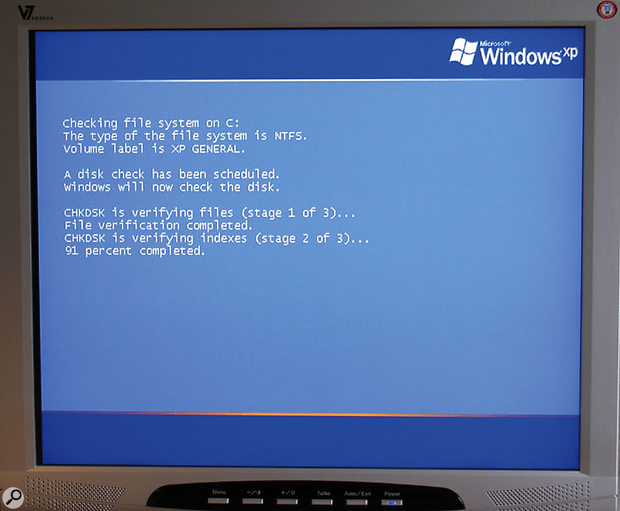

Hard drives are sealed to prevent dust getting inside, so physical

cleaning isn't necessary. However, the data they hold can be subject to

errors, so it's well worth doing some routine health checks using

Microsoft's

CHKDSK utility (supplied with Windows NT, 2000, and

XP). This utility runs automatically when you boot up your computer

after it's had any problems shutting down, has crashed requiring a

reboot, or after a power cut. However, it's sensible to run

CHKDSK

at other times to check for errors, and sort them out if any are found.

I suggest you do this routinely two or three times a year, as well as

immediately before defragmenting your drives (most defragmenters will

abort if drive errors are discovered).

The easiest way to access

CHKDSK is to right-click on a

drive partition in Windows Explorer and select the Properties option.

The dialogue that appears has a Tools page that includes an

error-checking option. You can use this to scan for possible errors, but

you can't, unfortunately, use the 'Automatically fix file system

errors' option while within Windows, since many system files will

already be open and therefore 'active'. An error message will pop up and

offer to instead run

CHKDSK the next time you boot up before Windows starts, just as it does after a crash.

If, for some reason, you can't run

CHKDSK on automatic

reboot, try running it from the Windows XP Recovery Console. First, boot

your PC from the Windows XP CD-ROM, and once the 'Welcome to Setup'

screen appears, press 'R' to launch the Recovery Console. If you have

multiple XP or 2000 installations, you'll next have to choose one to log

into.

With either of these alternatives you then need to type in the

appropriate text command. To scan for and fix hard drive errors you'll

need to type in 'chkdsk c: /f' and press return (change the 'C:'

parameter if you want to fix other partitions). There are also various

other

CHKDSK options. For detailed descriptions, pay a visit to

www.microsoft.com/resources/documentation/windows/xp/all/proddocs/en-us/chkdsk.mspx.

Once you've run

CHKDSK and it's discovered no errors, it's

the ideal time to defragment your Windows drives. Defragmentation is

essentially the art of rearranging files on your hard drives to enhance

performance, and the pros and cons of doing this on audio drives is a

complex subject that I discussed in great depth back in

SOS

June 2005 (see the 'Further Reading' box). However, there are nearly

always benefits to defragmenting Windows drives, such as both Windows

and its applications loading more quickly, and smoother general file

access.

When you delete files on your hard drive, all that happens is that

the entry pointing to the data is removed, leaving the data itself

intact. Although Windows will now happily save new data over the top of

the old, some of your deleted data may still be intact months or even

years after its deletion. Even reformatting your hard drive simply

removes its 'table of contents', and using suitable software tools you

could still recover much of it.

This can be a life-saver if you ever accidentally delete some data

you later want reinstated, but is extremely worrying if you have

personal information on your PC that you need to permanently erase, such

as client data, tax records, credit card numbers and web-surfing

history. A study by the University of Glamorgan on 105 hard drives

bought on Internet auction sites showed that data could be retrieved

from 92 of them, including passwords, National Insurance numbers, and

financial information such as sales receipts and profit and loss

reports.

Security experts say the only really successful way to ensure that

no-one can ever retrieve personal data from a discarded hard drive is to

drive a six-inch nail through it, crush it or incinerate it, but

utilities designed to securely wipe complete partitions and drives of

all their data by overwriting them a number of times with random

patterns of data do make the hacker's life a lot more difficult. So if

you want to permanently erase personal data from a hard drive, either

for routine personal security, before you sell it, or before you donate

your old PC to a local charity, it's well worth taking a little more

trouble to make sure your deletions are permanent. After all, identity

theft can be a costly business!

If you want to permanently delete the contents of an entire hard

drive, there are plenty of commercial products available, including the

$50 Acronis

Drive Cleanser (

www.acronis.com), the $30 Paragon

Disk Wiper (

www.disk-wiper.com), or the $40 VCom

Secur Erase (

www.v-com.com). One freeware alternative is

DBAN (

Darik's Boot And Nuke),

a self-contained boot floppy disk that you use to boot up the PC in

question. It will completely delete the entire contents of any hard

drive it can detect, making it ideal for use prior to disposal of a PC

but highly dangerous in the wrong hands.

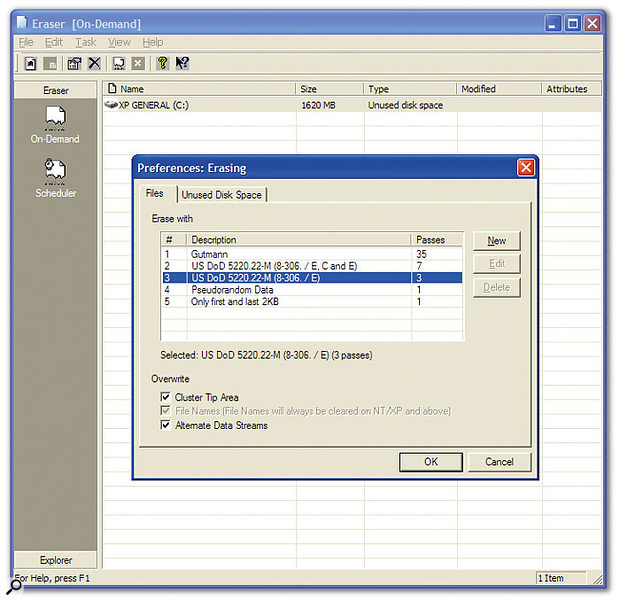

Since a number of passes are normally required for secure deletion,

it may take some hours to completely wipe an entire hard drive using

such utilities, but they should prove extremely useful if you or your

company periodically disposes of old computers. If, on the other hand,

you need to securely delete specific files, or want to 'clean up' the

supposedly empty areas of your hard drives on a more routine basis, I

can thoroughly recommend the Eraser tool (

www.heidi.ie/eraser).

It's free (although you can send a donation of a suggested 15 Euros to

support further development) and can be be run on demand to delete

specific files, folders or the empty areas of your drive, or be used

inside Windows Explorer as a right-click option instead of the Recycle

Bin or normal delete options. It also deals with 'cluster tips' (unused

areas at the end of the final cluster used for each saved file, which

may still contain data belonging to a file that previously occupied that

cluster).

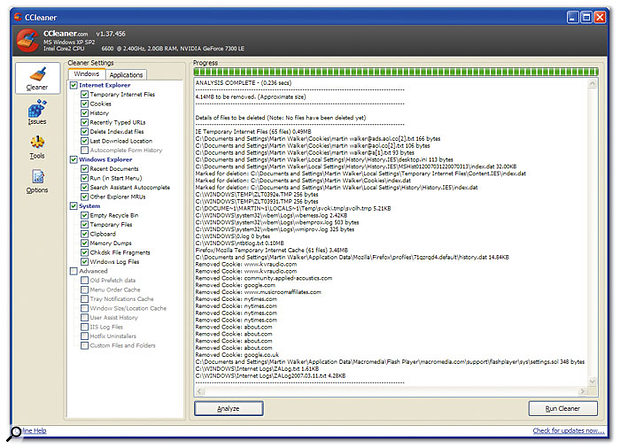

Even if your hard drive is healthy, it may be storing a considerable

amount of junk data that you no longer need. Temporary Internet files,

those left behind during software installs or by applications with

multi-step Undo functions, old backup files and unwanted log files can

soon amount to many megabytes unless you take steps to eradicate them.

You may also prefer to remove evidence of your Internet surfing

activities, including cookies and URL history files of sites you've

visited.

Windows XP includes its own Disk Cleanup utility, but it's not very

thorough. There are also plenty of commercial utilities that do better,

but the one I regularly use and recommend is

CCleaner (

www.ccleaner.com),

which runs with Windows 95, 98, ME, NT4, 2000, 2003, XP and Vista. It

cleans the Windows Recycle Bin, Recent Documents, temporary files and

log files, plus the temporary files, URL history and cookies from

Internet Explorer,

Firefox and

Opera browsers.

CCleaner also deletes temporary files belonging to many

third-party applications and offers optional secure deletion, with one,

three or seven passes, so you're certain of removing sensitive data for

good (although it doesn't eradicate the file names —

Eraser is

still more thorough in this respect). It also has a basic Registry

cleaner (more on this shortly) and, best of all, it's totally free! The

only area that

CCleaner doesn't cover is comprehensive scanning

for non-Windows junk files across all your drive partitions. If you

want a good clearout of these, Iomatic's $30

System Medic is

certainly versatile, offering a user-configurable list of junk-file

types, plus separately configurable lists of Inclusions and Exclusions

for specific folders, as well as a choice of which drives to include in

your searches. Such a utility can deal with many unwanted files

extremely quickly, but you have to be extremely careful what files you

include in its scans. It's very easy to accidentally delete all your

song backups, for instance!

Your Registry is another area where a good spring clean may reap

dividends, since it could potentially contain thousands of redundant

entries. Some Registry entries may point to non-existent files, and may

be deleted, or alternatively amended to point to the correct file, to

avoid crashes.

Although I'm against disabling Windows Services, since the measured

benefits are tiny but the risks of causing instability are great, my

experience with Registry-cleaning utilities is rather different. I use

several on a regular basis on my own PCs, removing rogue Registry

entries, followed by Registry compaction, either using a tool built into

some registry cleaners or the freeware

NTREGOPT (

www.larshederer.homepage.t-online.de/erunt),

typically reducing the size of my Registry by around 10 percent. This

can only improve Windows performance, but all the utilities I use

provide backup options, so if necessary you can reverse any Registry

changes you make.

In my experience, every Registry cleaner finds a slightly different

collection of issues, so I tend to run each in turn. First up is

Microsoft's own

RegClean (no longer supported by Microsoft, but still available as a free download at

www.soft32.com/download_239.html).

It's by no means as thorough as most other tools, but can remove a

significant swathe of redundant data on its first run and a smaller

amount on subsequent runs.

Next up is

RegSeeker (

www.hoverdesk.net/freeware.htm),

which, among its many other features, has a Clean function that always

finds lots of unused extensions and 'open with' references, as well as

references to non-existent files. Its excellent 'Find in Registry'

function is handy or stripping out all old soundcard references that

won't be removed by the standard uninstall routines.

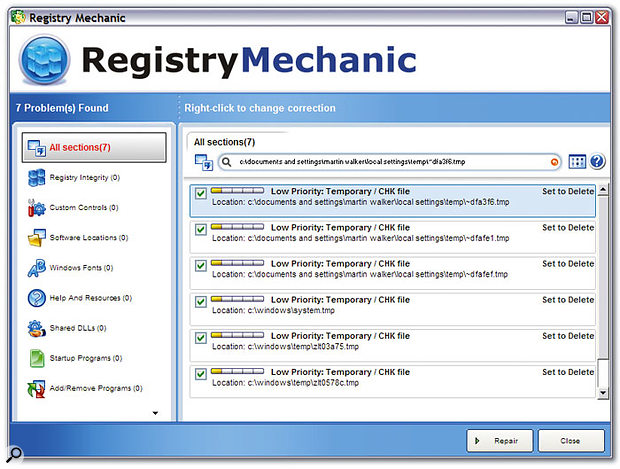

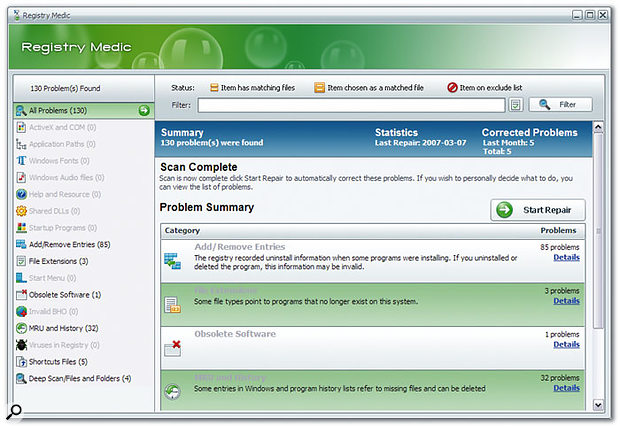

The other two utilities I use and recommend are Iomatic's

Registry Medic (

www.iomatic.com) and PC Tools'

Registry Mechanic (

www.pctools.com).

Registry Mechanic

offers a Smart Update function to ensure you're using the latest

version, a background monitor that you can use to spot unintended

changes to your Registry (although for optimum performance it's wiser to

disable this while running audio applications), an Optimise function

for applying various registry tweaks and a Registry 'compacting'

feature.

Registry Medic has similar features.